A whole host of cultural illuminati have lived or worked in Westport for a time. Famously, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald wrote, and Desi loved Lucy. More recently, Lynsey Addario and Justin Paul graduated from Staples High School and went on to do amazing things. We can lay claim to talented residents in myriad fields.

When the town graciously selected me as its first Poet Laureate, a question arose about which famous poetic forebears (I am decidedly not famous) might have lived or written in Westport. A subsequent search yielded surprisingly little. A rumour that I plan to research had it that Robert Frost may have alit here for a while, but that is as yet as unconfirmed as a Yeti sighting.

Never mind, I thought. What about everyday poets and poetry? Part of my mission as inaugural Poet Laureate of our hamlet is to make poetry less mysterious and inaccessible, and to create community through what we can all share through words. So I decided to dig a bit into Westport’s more quotidian poetic life. It turns out that we have a rich and quirky history of verse, created by many little-known, but homegrown, bards.

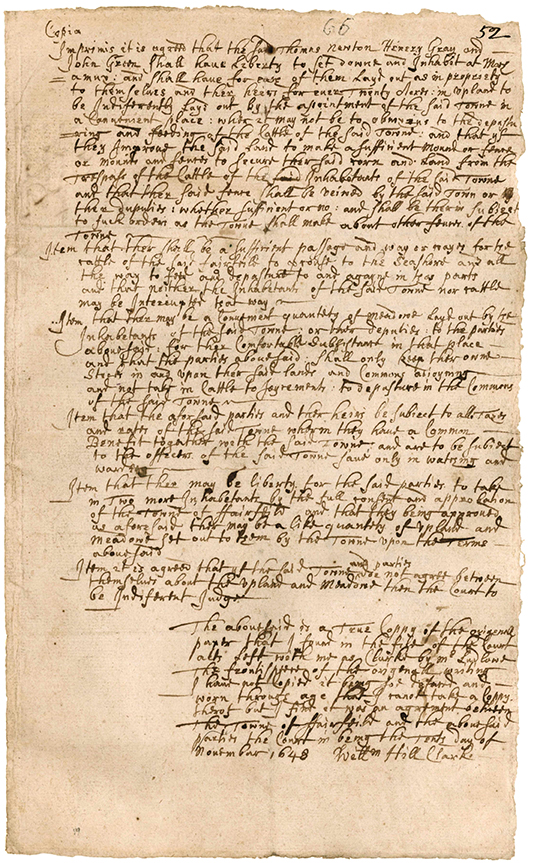

My research has been neither exhaustive nor scientific, but I have found a great deal of poetry in some unexpected places. The Westport Museum for History and Culture and the Westport Library both yielded quite a few surprising finds:

Autograph Books

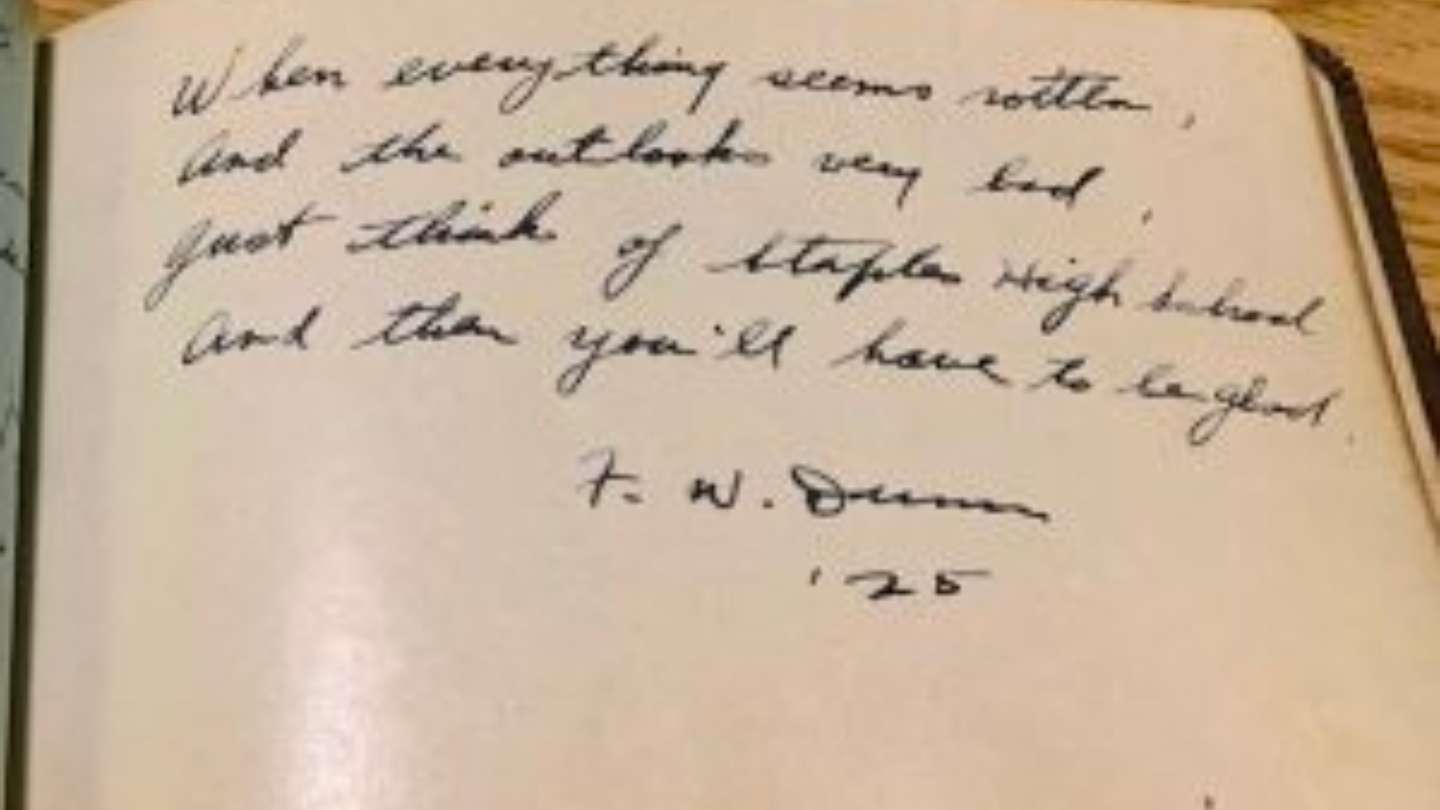

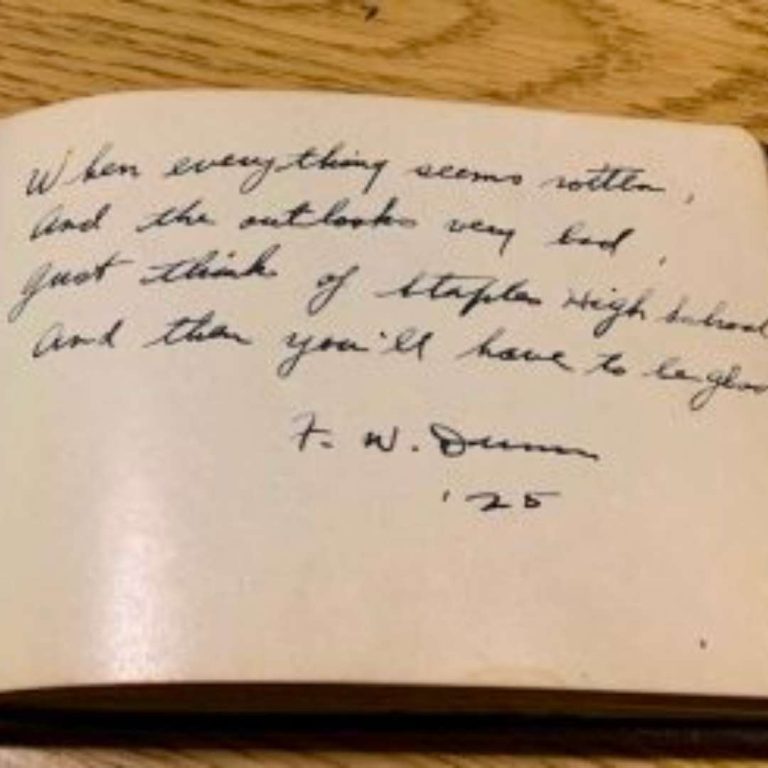

Back in the day, graduating seniors would bring small autograph books to school prior to the end of the term, and get friends to sign them. We often do this now with big, heavy yearbooks, but these fragile pages in the Westport Museum’s archives hold sentimental and endearing gems within their bindings.

In 1925, Marie Durner wrote: “When rocks & hills divide us/And you no more I see/Just think of the name ‘Midgie’/A school pal dear to thee”. F.W. Dunn philosophized: “When everything seems rotten/And the outlooks [sic] very bad/Just think of SHS/And then you’ll have to be glad”. And ‘Dint’ Maurer quipped: “Merrily we trot along/O’er the future ‘o path/But take heed! Don’t fall/For every fall means a step/Nearer to your grave.”

Image Courtesy Westport Museum Collections

Christmas Cards

For some neither the brief “happy holidays” nor the more voluminous ‘our family’s year in words’ would do. When some Westporters sent holiday greetings, they did it in verse. In 1946 Adelaide and Jack Baker wrote: “Far-flung adventures? None this year/Those who are building cannot roam/Shingles and brick and plumbers are/Elusive, so we stayed at home/And, as we made new homes for others/Found that our own was still more dear”. The Sanford Evans family sent this Christmas greeting in 1925: “Our chimney pots/Are good and big – and our/Yule-logs burn with cheer/For all that/We’re expecting – Are they/Big enough this year?” And in 1933 The Steinkraus Family put out Ye Westport Primer, with a seasonal abecedarius printed in red and green, beginning with “A is for artists you see all around;/This is the town where they do abound/ B is for the beach, a fine place to swim;/We loll on the sand to get vigor and vim”, and ending with “Z’s for the zassafrass in our backyard,/(You’ve got to admit that Z’s very hard.)” Christmas illustrations, including Santa in his reindeer-pulled sled flying across a red full moon, abound.

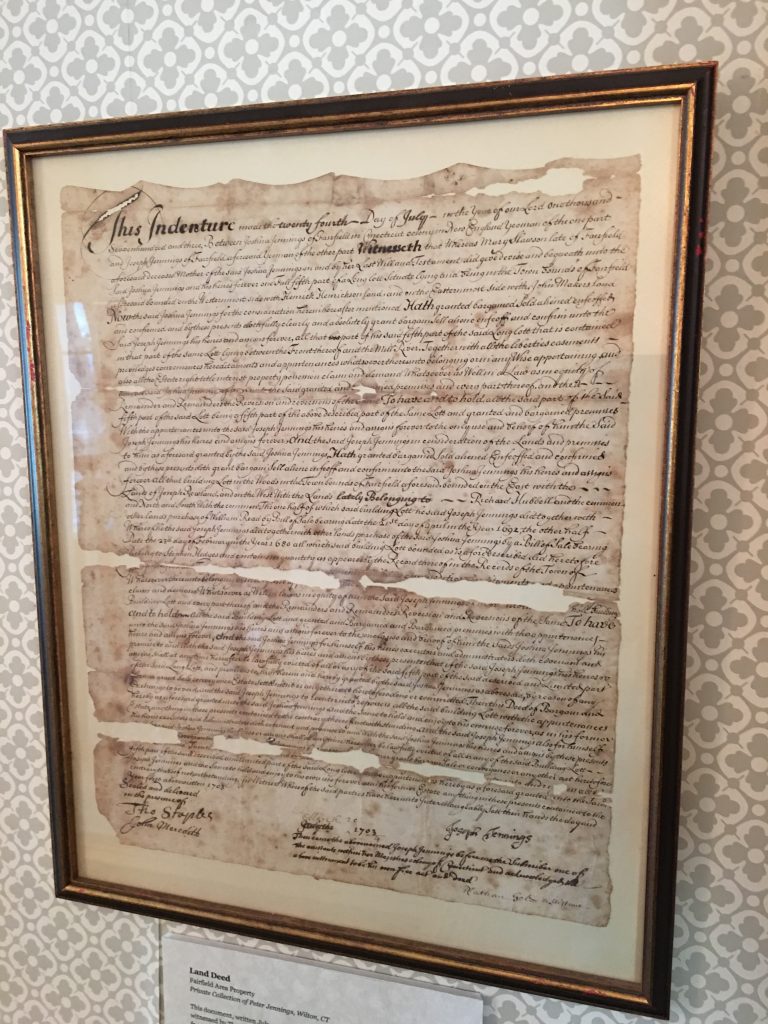

Town Clerk

In the 1867-1886 volume “Births Marriages Deaths for Westport, a creative Town Clerk included some lovely verse in the blank spaces of the ledger where he recorded the quotidian events that made up our townsfolk’s lives. He harkens back to the eighteenth-century poet George Crabbe who had, a century earlier, also recorded the lives of his fellow villagers in rural England, and shares his words, perhaps to reflect his own emotions, on several pages of his recordings. One, from 1834 is an excerpt from Crabbe’s The Parish Register and, reads: “To Muse, I ask, before my view to bring/The humble actions of the swains I sing/How pass’d the youthful, how the old their days;/Who sank in sloth, and who aspired to praise/Their tempers, manners, morals, customs, arts/What parts they had, and how they employed their parts/By what elated, sooth’d, seduc’d, depressed/Full well I know the records give the rest.”

Gravestones

Poetry comes to us from beyond, or more precisely from, the grave in some cases. While most of the headstones in the numerous cemeteries around town provide the most basic information – names and dates – some loved ones memorialized those they lost with verse. While these poems may not have been penned by locals, they were placed by locals, where they have served to sprinkle lasting poetry around town. In Willowbrook cemetery, in a quiet corner overlooking Main Street, a stone book lies atop a large column memorial for Julia Snowdon Hotchkiss. Its open pages reveal an anonymous quote often referred to by revered rabbis: There is no death/What we call death/Is but surcease/From strife/They do not die/Whom we call dead/They go from life/To life. Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s words from The Little Prince grace Marla Seigel’s pink granite marker: “In one of the stars I shall be living/In one of them I shall be laughing/And so it will be as if all the stars were laughing/When you look at the sky at night.” Hilaire A. Roth rests beneath Robert Burns’ verse from his poem A Red, Red Rose: “So fair you were, my bonnie lass/So deep in love was I/And I will love thee still my dear/Till all the seas go dry.” It surprised me to find so much poetry nestled amongst the much older and less crowded together, albeit virtually unreadable, headstones in the Greens Farms lower cemetery. Time, wind, water, and moss have erased or obscured much of the script, but some remains clear. For instance, Dorothy Z. Thompson’s family laid her to rest beneath the first lines from Walt Whitman’s A Clear Midnight: “This is thy hour O soul/To fly free among the stars/And ponder the themes/Thou lovest best.” Ghosts of poetic lines adorn, too, the headstones of Betsey Smith and Eliza Whitehead.

Local Authors

If it’s too chilly or muddy or buggy to tramp through local graveyards in search of bards’ words, head to the library and make your way downstairs to the poetry section where ‘local author’ stickers affixed to certain books’ bindings will lead you to homegrown balladry. Westporter Steven Herz composes paens to a painful time in his Marked: Poems of the Holocaust, and our town features prominently in Jonathan Towers’ Westport Poems. And although Regan Good may now reside in Brooklyn, her second collection of poetry, The Needle, harkens back largely to her childhood here in Westport. In the Westport Museum for History and Culture you will find a poem by Robert B. Northrop’s grandfather Robert DeWitt Allen dated March 30, 1900, describing a treacherous schooner trip up the Saugatuck. Captain Sam Allen piloted the Henry Remsen with a steady hand in this excerpt:

With all aboard and under way,/White water in her scuppers lay./Then stood her in around the bluff./He got her in near Eno’s dock,/But could not get by Judy’s rock./That night the wind came in nor’west,/But Sam just raved and could not rest.

— Robert DeWitt Allen

Sara Krasne, the Museum’s Archivist, reports that “Judy’s Rock probably refers to Judy’s Point which was originally called Judah’s Point after David Judah (the first Jewish person to live in Westport).”

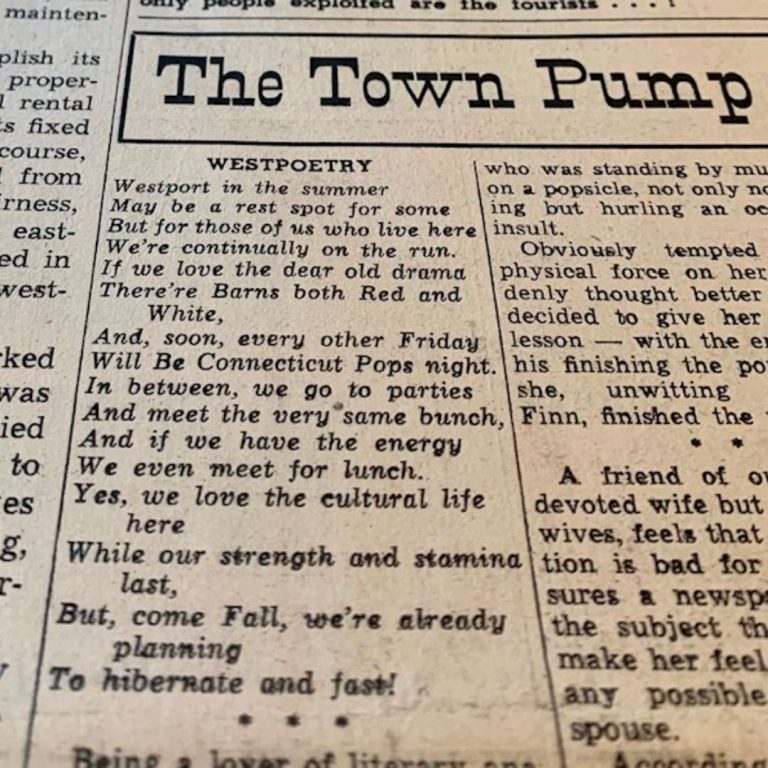

Local Newspapers

Not far from the poetry section you will find several immense, heavy black leather-bound tomes, in no particular order, stacked on the bottom of one of the metal shelves. Open these to travel back in time to the mid-century past and thumb through the yellowing and fragile pages of Westport’s local newspapers. Features like “Pupil Patter”, “Poems by Pat”, and most prolifically, “Town Pump”, feature original verse by poetic locals.

You will also find news stories about local elementary school poetry competitions, observations of poetry month, and even a poetic letter to the editor of the Westport Town Crier and Herald (July 5, 1957).

Poetry Box

One local resident in particular does her part to promote Everyday Poetry every day. Donna Ryzinski, who holds an MFA from Goddard College in Vermont, has for the last decade participated in a poetry reading group. Every other week these poetically inclined women congregate and recite a preselected poet’s verse. Each member, the oldest of whom is ninety-five, selects the featured poet and hosts the gathering on a rotating basis. But Ryzinski has taken this love of verse one step – or about three to be exact – further. Roughly that many paces off Sturges Highway in front of her home stands a small wooden box atop a matching post. Her husband fashioned this “best Christmas gift ever” from the door of an Upper West Side brownstone door. About the size of a large toaster oven, a front door of glass faces the street. Since 2015, she has placed a poem inside for all passers-by to stop and read. She prints off and changes the contents roughly once a week, and chooses from a wide variety of poets, as does her poetry reading group. The day I visited it featured a poem by local, well known poet Sophie Cabot Black. Ryzinski says that the poetry box brings her as much joy as she hopes it brings her visitors. She has witnessed two women scale a steep snowbank to access the verse within. One person approached with the reverence of a walking meditation and stood in tadasana (mountain pose) before accessing the words. A woman left tulips and a note: “Thank you for making my walks that much better”. And a gentleman stood in the driveway shouting, “I love this! Never stop doing this!”

It seems that while no wildly famous poets have made Westport their permanent home, many of their words have alighted here through our many poetry-loving residents. Moreover, many of them have created their own “words, words, words” (Hamlet, II.ii) of their own which, while may not have reached the audience of a Dickenson or Whitman, nonetheless imbue our little hamlet with the spirit of poetry.

In my role as Westport’s inaugural Poet Laureate I hope to tease out, encourage, and spread poetry around, knowing that it creates connection and community.

Special thanks to Sara Krasne for her assistance in researching this article.