During President’s Day—and week—we hear many a story about the glory of George Washington. Today, historians are taking a holistic approach to viewing historical figures—observing all aspects of their life, in as much as the available record allows.

One such interesting aspect was that the first President was the victim of an aggressive media troll. Propelled almost single-handedly by an individual acting as the tool of others, the attacks on the first President actually encouraged readers to go to the presidential mansion in Philadelphia to shout epithets and threats.

The troll was Benjamin Franklin Bache, grandson and apprentice of the more famous Ben Franklin. Bache published the Philadelphia Aurora newspaper and used it to print accusations largely based on information sent to him by those who opposed Washington’s policies.

Back then, before the brief heyday of objective journalism some centuries later, there was nothing to stop Bache from excerpting material—or even lying—to create the story he wanted to tell. Without independent editorial oversight, his paper functioned very much like that of some modern-day “news” outlets: unchecked, heavy on opinion and bombast.*

Yet Washington kept his own counsel—confidant that Bache’s unfounded fury would eventually fade in the light of the truth. Although, for more than a year after Washington retired, Bache continued his libelous attacks until his own death of Yellow Fever in 1798 at age 29.**

Benjamin Franklin Bache

Why was Bache so against George Washington? In part, because of Bache’s own self-importance—Bache was enraged that Washington refused to grant him (and others like him) fame and position in deference to the achievements of their famous forebears. But Washington was staunchly opposed to patronage—believing that just because things usually went someone’s way didn’t mean they always had to.

Another reason for Bache’s pseudo-journalistic assaults was that he considered Washington an “outsider.” He did not believe Washington, a Virginian, to be “one of them”. To Bache, Washington was an interloper who was not a “real” Philadelphian. To Bache’s mind, Washington’s work on behalf of the republic paled because the first president simply didn’t “know his place.”

Today, the “us” vs. “them” of that era is portrayed clearly: “us” equals patriots and “them” equal the British. Yet, truthfully, only one-third of the nation supported Revolution, while another third opposed it and the remaining didn’t care either way.

For Washington whose father’s untimely death cost him opportunities in status and education, “them” specifically comprised people whom he believed had more chances than he did and, later, his political rivals. In larger American society, “them” equaled native people, enslaved Africans, other people of color and women.

For Bache, “us” equaled those other supercilious persons who, like him, believed in their own exalted significance. “Them” were all who failed to be cowed by the malevolent bludgeon of his publication. Bache’s 18th century the language of othering people into “us” and “them” took the same predictable forms as today: “not one of us”; “not really from here” and “who does that person think they are?” All were used by Bache in some form.

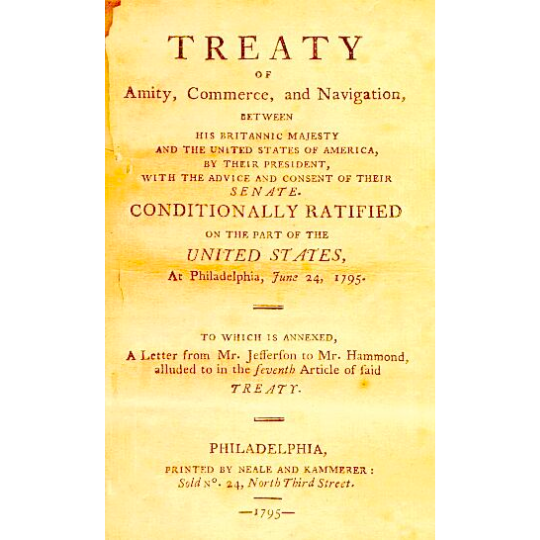

First page of the Jay Treaty

Ultimately, Benjamin Franklin Bache was most skillful at tapping into his readers’ fear of change, couching personal attacks on Washington within social questions guaranteed to trigger outrage. When Washington decided America should remain neutral during the French Revolution, Bache accused him of disloyalty to a trusted ally. It was an observation that didn’t explore the other side: America’s potential reputational damage supporting a frenzied, blood-thirsty revolt.

And again, in 1795, Washington felt he had no choice but to sign the Jay Treaty to avert another war with Britain, Bache obtained a copy of the Treaty and pre-published it to tap residual anti-British sentiment—ignoring the legitimate financial reasons that necessitated agreement. Later, Bache went so far as to publish forged documents implying Washington’s motives in the Revolutionary War were entirely self-serving.

Yet, the truth was that Washington was making hard, unpopular, decisions to protect the infant United States from chaos and financial ruin. In so doing, it’s easy to imagine he was following an admonition he wrote to himself as a teenager in a small diary he entitled Rules of Civility–and continued to follow in his life as a military commander, politician and Free Mason:

labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience

Join us to learn more interesting and unusual facts about President Washington at our Ale to the Chief Washington Beer Bash on his birthday, this Saturday, February 22.

* Kohn, George C. The New Encyclopedia of American Scandal, Benjamin Franklin Bache: Vengeance Through Journalism p20 Facts on File, 2000.

** Benjamin Franklin Bache, mountvernon.org