“We the undersigned residents of 22 ½ Main street, respectfully petition the town government to help us secure decent, low-rent housing for ourselves and our families.” As reported by the Westport Town Crier on December 22nd 1949, these words formed a petition from the residents of the building which housed 70 people including four WWII veterans which was presented to the Westport Board of Selectmen.

In honor of Black History Month, we will look into the plight of the residents of 22 ½ Main Street. These residents made up the lion’s share of Westport’s African-American population, many of whom had been in the community since the 18th century when their ancestors were enslaved. The building at 22 ½ Main Street was the epicenter of a neighborhood that existed in alleyways between Elm Street and Main street with “1/2” numbers for their street addresses. The residents of 22 ½ Main Street represented citizens originally from the South who had come north to communities like Westport to seek work in what later became known as the Great Migration.

It was a community that fought to survive in the heart of Westport, despite those who sought to exile them.

The Town Crier reported that 70 people were living at 22 ½ Main Street, and just a few months earlier in March, a doctor who had been sent to the housing complex reported that he found 24 people living in 25 rooms. Dr. C. W. Gillette had been assigned to ascertain whether the complex were the source of a public health menace by First Selectman Albert T. Scully. It seems that “concerned citizens” of the town were worried about overcrowding and unsightly conditions in the courtyard off Main Street.

The town prosecutor’s office initiated complaints via a declaration of violations which stated that “a serious condition, perilous to their health and morals and to the town as a whole,” exists at 22 ½ Main Street. Although the statement was harsh, it didn’t mention slum conditions in any other part of town.

Town officials couldn’t get behind any of the various solutions offered over the years, though the “slum conditions” of 22 ½ had been considered a problem since before WWII. The idea of closing the building was often proposed, but the town officials didn’t know where the residents would then live, so they kicked the proverbial can further down the road for the next group of people to try to solve.

Through all of the controversy, the building’s owner, Mr. Peter Guglieri, said that he had offered to make whatever improvements to the building that the town officials would suggest, if they would only assure him that the current tenants wouldn’t be moved out after the improvements were made. He also stated that he didn’t know of any violence or illegal activity occurring on the property. So the question of conditions “perilous to the morals of the town”, as the prosecutor’s office stated seems questionable at best.

The few records and newspaper articles that exist about this settlement seemed to indicate the residents were hardworking, God-fearing folks that were just trying to get by in a town that was caving into the pressures of a Jim-Crowe era society. In several city directories, the Antioch Baptist Church, sometimes listed as the “Westport colored church” was at 28 Main Street or 22 ½ Main Street. The pastor was listed as a resident of New York and it is surmised that he may have been a traveling preacher that would commute to Westport for the weekly services.

In December 1949, an RTM meeting was held and a heated debate ensued about public housing and who would be eligible to apply. A group of African Americans, mostly those living at 22 ½ Main Street attended the meeting and their elected spokesperson was Mrs. Roscoe Richardson. She was at first rebuffed by the moderator, but after the crowd began to chant “let her speak,” her statements were heard. She described their living conditions as a “slum”.

The Housing Authority Chairman, Mr. Charles Cutler, answered Mrs. Richardson’s speech by stating that the “Negro delegation” would be eligible to apply for the rental of units in the new housing project, after the needs of veterans were taken care of, and further he said that two of the forty-two families being considered were “Negro families.” From the Town Crier’s reporting, this seems to have been enough at the time to satisfy the crowd.

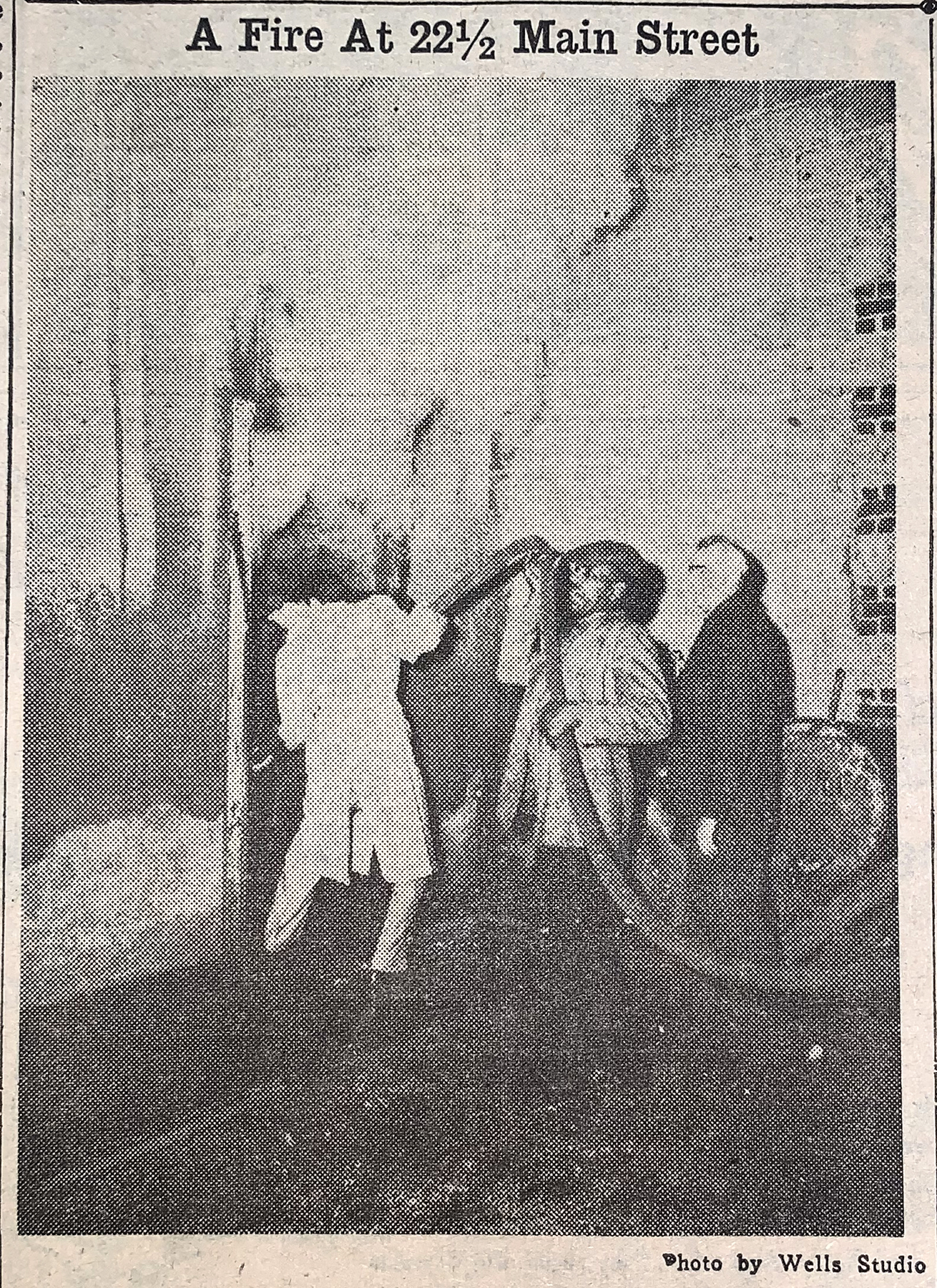

This political cartoon accompanied an opinion piece in the January 26th, 1950 edition of the Westporter-Herald

In the article, Mr. Barmmer points out that the Fire Department could condemn the “shacks” and then a Federal grant could be applied for to pay for building new housing on the same or similar site. He goes so far as to posit the question “if a fire was to break out there tonight when all occupants were asleep – we wonder how many would escape alive?” Just 8 days later, a fire broke out in the section of the building used as the Antioch Baptist Church. Everyone made it out alive, but most of the structure and nearly all of the residents’ possessions were destroyed. Had one of the residents who lived adjacent to the room from which the fire emanated, Mr. Robert Hall, not awoken, the outcome could have been much different.

In the January 26th 1950 edition of the Westporter Herald, a political cartoon depicting those residents of 22 ½ Main Street as “enslaved” to the “slum housing” appeared along with an opinion piece written by Russell Barmmer about what could be done do provide low cost housing to those residents.

When Westport Historical Society asked if the Fire Department could find any records from the time about a fire investigation at the property as arson, none could currently be found. This may be because they did not survive the test of time, or perhaps that no real investigation was done. Because this area was considered a blight on downtown, it seems many saw the fire as a “good riddance” situation.

Newspaper accounts paint the picture that the people living at 22 ½ Main Street recognized that their living condition was poor, that the owner of the building knew it, and that the town leaders knew it as well. It’s a sad comment on history that the only “solution” came via the destruction of the building.

Some families stayed in the unburned portion of the building for several months trying to find alternate housing but, in the end, almost every single person who had lived there moved on.

Mrs. Sheila Johnson gave an interview to the Westporter-Herald which appeared in the May 25th, 1950 edition of the paper, in which she says “I guess Westport has finally succeeded in getting rid of us… well, I hate to leave the Town, my Mother lived here 20 years you know and I have been here 18 years. But maybe it’s for the best. There’s no use staying where you’re not wanted.”

This heartbreaking statement echoes through the years. These Westporters only wanted to live in clean, affordable housing. Was that really so much to ask?

To learn more about the history of African-Americans in Westport please visit our online exhibit portal featuring the award-winning exhibition Remembered or email archives@westporthistory.org with questions or to schedule a research appointment.