The “House on The Pond” is recognizable to many Westporters but from about 1919 to 1940, the lady who lived there – Lillian Wald – was even more famous still. A nurse and humanitarian most noted for her work among young people and with immigrants in New York City’s Lower East Side, Wald was a noted pioneer of American public health.

Born 10 March 1867 in Cincinnati, Ohio to German-Jewish parents Miss Lillian D. Wald, got her first taste of nursing when she was eighteen years old assisting the nurse her elder sister Julia had hired after the birth of her first child. Lillian’s interactions with the independently helpful woman sparked in Lillian a passion that would last a lifetime. Lillian resolved to become educated as a nurse and was accepted to the New York Hospital School of Nursing in 1889. After her graduation in 1891 she spent a brief time working in the New York Juvenile Asylum on West 176th Street in Manhattan. After seeing deplorable conditions and suffering exceedingly ill treatment of patients by medical staff, she determined a medical degree would gain her the respect and abilities to effect change for the youth of the city. In 1892 she enrolled at the Women’s Medical College (WMC) in New York City.

While enrolled at the WMC, Lillian volunteered to teach a home-nursing course to immigrant women from the Lower East Side. One morning, the daughter of one of her students came to fetch Miss Wald to assist her mother. The child rushed her through a series of side streets and alleyways until reaching a tenement on Ludlow Street. Then Lillian was led across a court, past open toilets to a rear building. There, the family of seven and two boarders were living in two rooms and the sick mother was lying on a dirty bed, suffering from a two-day old hemorrhage. The sight of this woman’s plight and the shock of seeing how many humans lived in similar conditions were the catalysts to change Lillian Wald’s future life. After this experience, Lillian found that she could be useful without a medical degree and decided to leave WMC.

With the help of Mary Brewster, a friend from nursing school, she acquired an apartment in a Jefferson Street tenement. The two began going about the neighborhood to help with the sick regardless of their religion or their ability to pay.

Lillian Wald with former UK Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, his daughter Ishbel and Lillian’s dog, Ramsay at her home on Round Pond Rd, Westport, CT, 1929; WMHC Collections

Soon, however, Miss Wald and Miss Brewster found that they had more work ahead of them than just the two ladies could handle, and so they increased their number to four and in 1895 moved to a house at 265 Henry Street which was donated by Jacob Schiff and would eventually become the Henry Street Settlement and Visiting Nurse Service.

Twenty years after Miss Wald initially arrived on the East Side, the Henry Street Settlement housed two kindergartens, carpenter shops, dancing schools, gymnasiums, debating classes and literary societies, as well as having three summer homes in the country for patrons to visit, a convalescent home, a library and study, and a place set aside for a sewing school. They offered lectures on subjects which ranged from government to sex hygiene, and there were clubs for boys and girls.

Over the years, Miss Wald became involved with numerous humanitarian efforts. She worked with the Board of Health to post nurses in schools and by 1914 had succeeded in having 374 school nurses city wide. Also, she and others formed the National Child Labor Committee in 1903. In 1905 Lillian met with President Theodore Roosevelt and suggested the idea of creating the Federal Children’s Bureau which would help educate and protect children in the workforce. The Bureau was eventually formed, but not until 1912 by President Taft.

Lillian also helped to establish the Nurses Emergency Council during the influenza Epidemic when it struck in the fall of 1918, at a conference of nurses called by the Red Cross Atlantic Division. Perhaps one of her most well-known contributions to society was her suggestion to Dr. Lee Frankel of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to send trained nurses to the family of every policy holder where insurance representatives had reported illness. This visiting nurse service was approved by the Met Life board and speedily implemented not only in New York City, but to all policy holders throughout the United States and Canada.

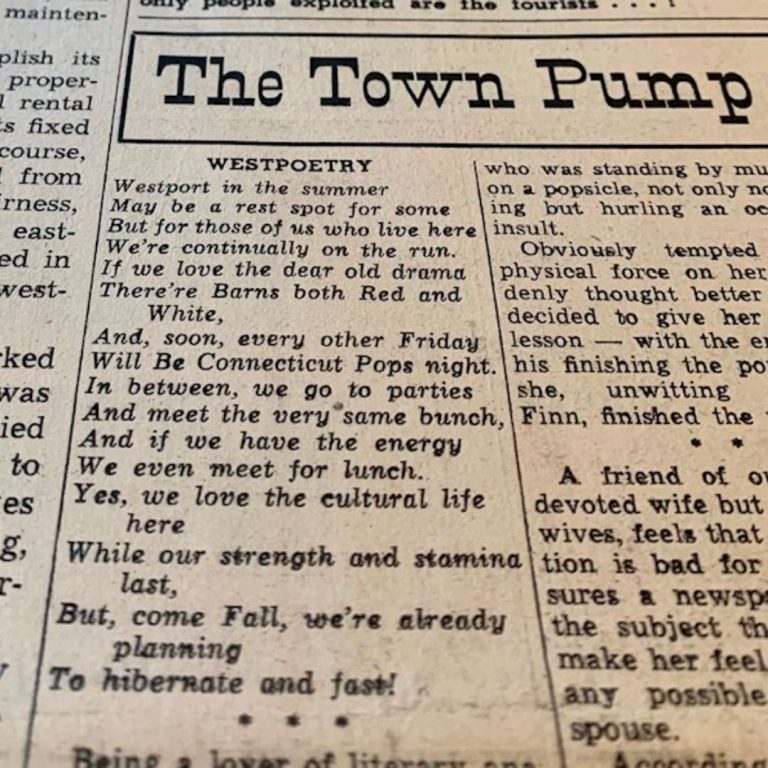

Toward the end of WWI, Lillian rented a home for her ill mother to convalesce in during the summers on a small pond near the Saugatuck River in Westport. After her mother’s death in 1923, and after her own health began to decline in 1925, Lillian continued to summer at “her house on the pond” which she then purchased. Lillian retired from active work at the Settlement in 1933 and relinquished the presidency in 1937. However, her retirement was not spent quietly as she entertained many of her famous friends at her Compo home. Chief among them were Jane Addams, Albert Einstein, Former Mayor of New York City Fiorello LaGuardia (a fellow Compo resident), Governor and Mrs. Herbert Lehman, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald with his daughter Ishbel, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

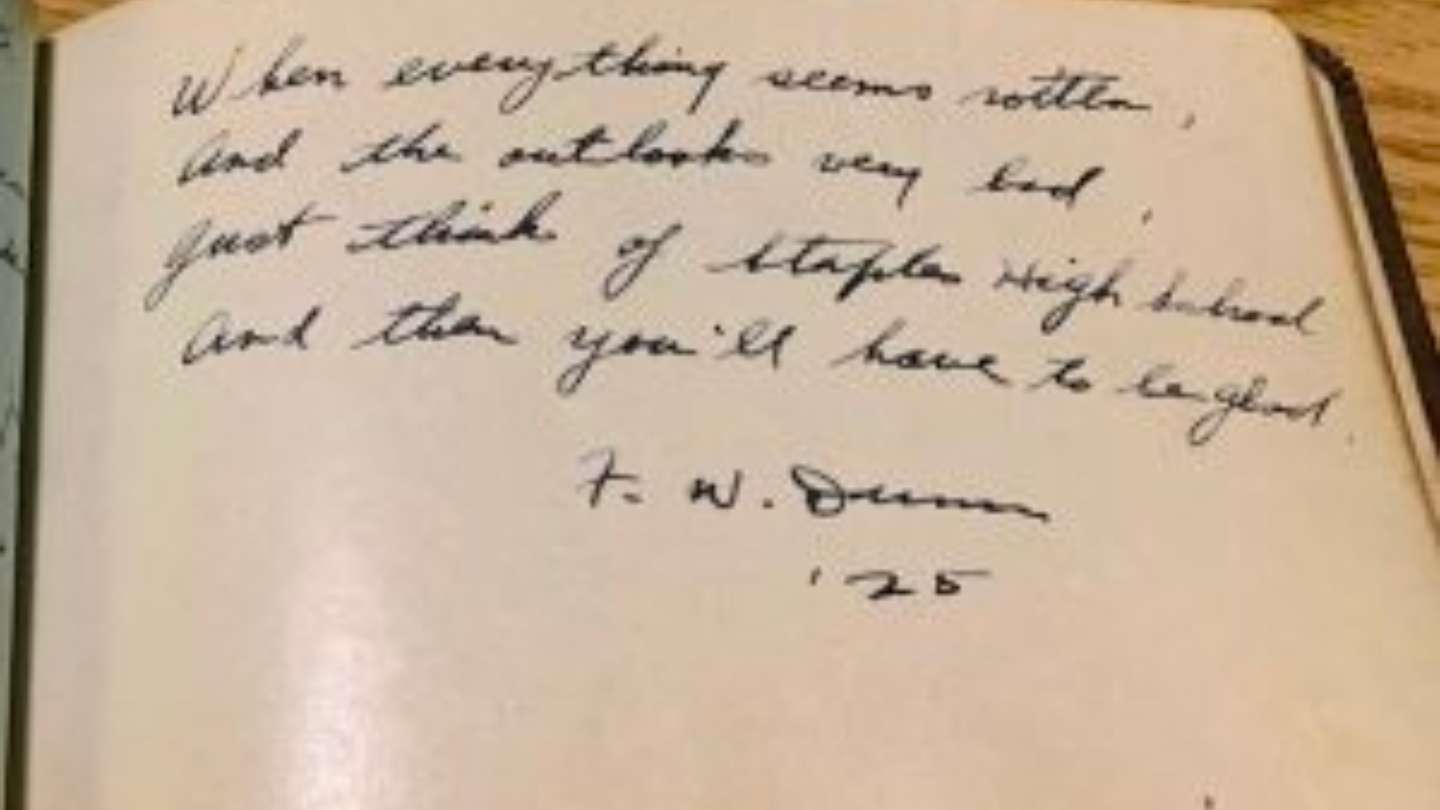

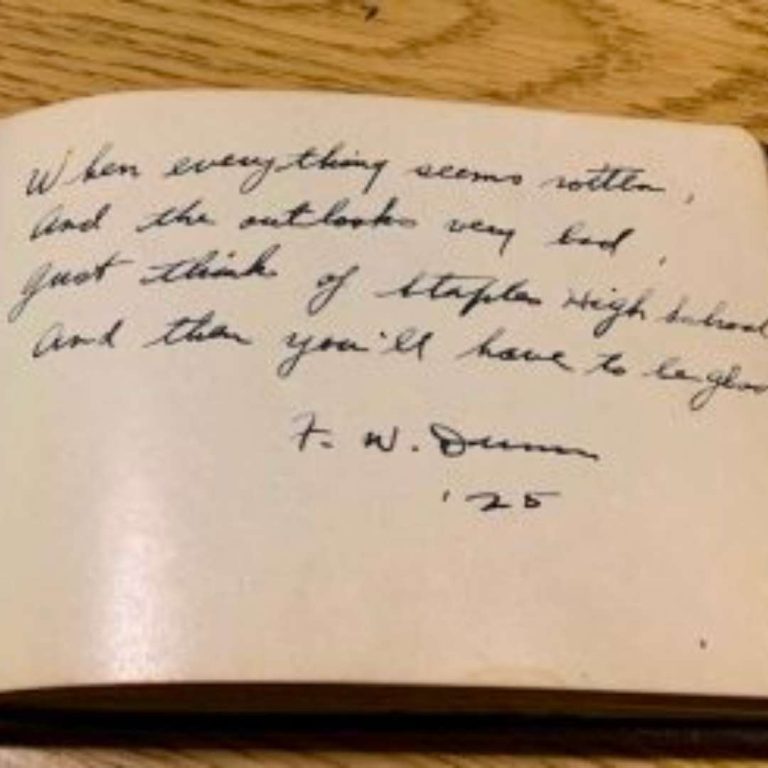

For her 70th birthday in 1937 and the 20th anniversary of her residence in Westport, a book of words, signatures and illustrations was compiled by the members of the community. 1200 of Westport’s men, women, and children signed the book or provided illustrations. Each contributed $0.25 to make up a check for the Henry Street Settlements.

Lillian Wald with Jane Addams in Washington, D.C., 1916; Library of Congress Photo Collection

This unique book was cherished by Miss Wald and its pages were preserved at her request. Local artists who contributed to this book were James Daugherty, Charles Prendergast, Robert Lambdin, George Wright, Alice Harvey, Kerr Eby, Karl Anderson, Beulah Allen Northrup and Joe King. This book is now on display at the Henry Street Settlement and a facsimile copy was made and bound which can be viewed at the Westport Library.

Miss Wald remained active while in Westport, willing to help with local relief programs, and she maintained a phone on her bedside table so that she could be in constant contact with welfare and relief organizations. And in her last months, although she was quite ill, she instructed workmen to install flood lights around the pond so that the children who were apt to skate there in the evenings would be able to see.

Lillian Wald passed away September 2, 1940. Westport mourned her passing and many of her friends and neighbors pushed and eventually succeeded in her election to the Hall of Fame of Great Americans at New York University in 1970.

You can learn more about Lillian’s life and work by reading her books, The House on Henry Street and Windows on Henry Street or by visiting the Henry Street Settlement in New York City or by viewing their online exhibit at TheHouseOnHenryStreet.org.